EVERYTHING You Ever Wanted to Ask About Biodiversity Net Gain

What is Biodiversity Net Gain?

Since the Environment Act gained royal assent in November 2021 and passed into UK law, biodiversity net gain – along with other core policies – has become a consideration that developers will be required to adhere to in current and future developments.

The principle of biodiversity net gain (BNG) is to deliver a habitat quality and quantity enhancement on or off the pre-development site as part of biodiversity offsetting following the completion of new development projects.

It is possible to measure biodiversity – both the current pre-development biodiversity value and the projected post-development biodiversity value – on a development site using the latest version of the DEFRA biodiversity metric from the responsible body.

The biodiversity net gain policy sets to mandate net gains for biodiversity across all future development proposals in England, including major nationally significant infrastructure projects and private planning projects on smaller development sites.

By following the biodiversity net gain requirements, the architect, developer, planner or project manager can make certain alterations to the development proposal to ensure that the outcome of the project causes a net gain in biodiversity. As a result, local planning authorities will possess all they need during the crucial decision-making process to see planning permission granted on the site.

Where Did BNG Come From?

Previously, biodiversity was protected by legacy laws transposed into the UK from the European Union, including the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 as amended, the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006, and the Town and Country Planning Act 1990.

Moreover, the concept of using a planning policy requirement to secure enhancement to the natural environment has been around since the inception of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in 2012 (since revised in 2018 and 2019), in section 175(d), as follows:

“Opportunities to incorporate biodiversity improvements in and around developments should be encouraged, especially where this can secure measurable net gains for biodiversity.”

Source: NPPF (2019)

However, in an effort to enhance the natural world to a measurably better state – and as a side effect of the country losing existing protections from the European Union following the UK’s departure as a result of Brexit – mandatory biodiversity net gain is a government response that will ensure new developments only go ahead if any unnecessary disturbance or destruction of natural habitats and biodiversity loss are strictly prevented.

Under this framework, not only will any impacted natural assets on the site be reversed back to their original general condition, but a mandated biodiversity net gain approach will ensure that they are improved upon to a superior standard of relative biodiversity value with adherence to blue and green infrastructure.

Rather than damaging the environment, ecological features, priority habitats, air quality from air pollution, veteran trees and overall biodiversity value, the Environment Act 2021 will maintain the suggested structure that the government announced in the new Environment Bill, following the prior unveiling in the 2019 Spring statement.

In essence, the primary objective of the new legislation is to carry out land management and environmental management in a sensible and sustainable manner, retaining irreplaceable habitat sites and sections of ancient woodland, enhancing habitats, combatting the effects of climate change and ensuring that local authorities, the UK government, Natural England / Natural Resources Wales, the British Standards Institute (BSI) and other governmental and non-governmental organisations are suitably happy that the planning process is being followed accordingly.

How Does Biodiversity Net Gain Actually Work in Practice?

Mandatory BNG will be delivered through the planning system of the corresponding local planning authority committing the developer to biodiversity enhancements that sufficiently equate to a net gain of 10% or more.

Although the government have confirmed that biodiversity net gain is undergoing a two-year transition period – meaning that it may not in fact apply until it is universally enforced in November 2023 – many local planning authorities are already following BNG guidelines based on local circumstances in preparation for nationwide acceptance.

It is worth noting, however, that in September 2023, the enforcement of BNG was pushed back once again to January 2024 before eventually releasing in February 2024. As such, it would be advisable that anyone with proposed development plans follows the new rules of biodiversity net gain and intends to deliver BNG, even prior to the end of the transition period.

Based on the strict 10% net gain increase, the next question might be, well, 10% of what? That’s where BNG metrics (versions of different metrics discussed below) come in.

As an integral part of the planning application stage, you will ordinarily need to provide strong support of evidence to achieve acceptance of planning permission by demonstrating a net gain of biodiversity present. Further details from development projects are best retrieved via baseline ecological survey data from a form of existing habitat survey.

Uncovering further information about ecological networks, a BNG assessment will integrate all present habitat types on a local level, and often involve attributes of other ecology surveys, such as a Preliminary Ecological Appraisal (PEA) or an Ecological Impact Assessment (EcIA). The Environment Act, however, requires that this biodiversity net gain survey includes a British standard assessment using the appropriate metric to quantify the level of biodiversity on your site in what is referred to as biodiversity units or statutory biodiversity credits.

Say, for example, your existing site has been assessed as having ten BNG units. Achieving a 10% biodiversity net gain and assuming avoidance of other issues that could contribute to unwanted net loss means that your completed scheme will have to deliver 11 units to ensure that the development project increases the habitat site value to meet the required relative baseline value.

Usually, you will need to instruct an ecologist on the back of your planning application to produce a net gain plan in order to secure the extra biodiversity unit, and either discharge your conditions of planning requirements or, in the same way, achieve release from a section 106 agreement.

What is a Biodiversity Net Gain Plan?

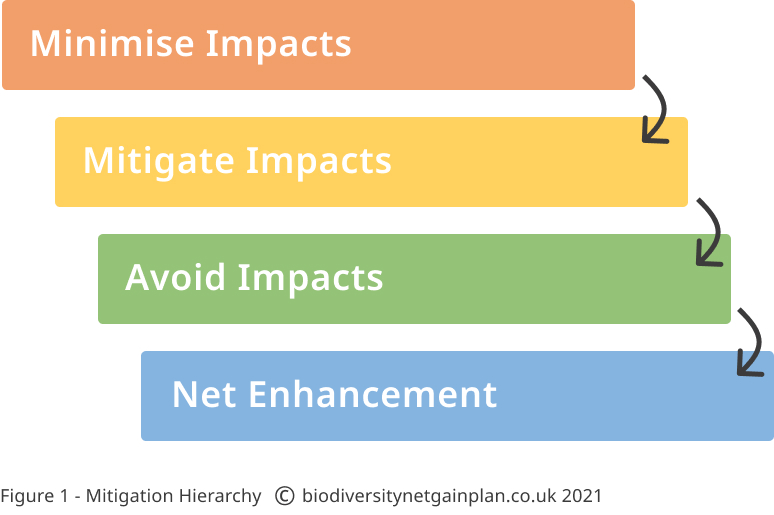

Biodiversity net gain plans are simple, plan-led management and enhancement documents that demonstrate to the local planning authority exactly what units will be created and over what timescale. During a biodiversity net gain assessment, an ecologist will begin writing reports specifically produced using the mitigation hierarchy to determine suitable next steps that will appease the local council, prompt measurable improvements to improve biodiversity and enable your project to continue as planned.

Following the biodiversity net gain survey, the ecologist will develop an effective plan with pragmatic solutions to ensure that the rules of biodiversity net gain are followed, biodiversity gains are achieved, the 10% increase in biodiversity is met, and the local council have enough evidence to accept unequivocally that your development project resides comfortably within the guidelines of the policy.

While each biodiversity gain plan will be created on a case-by-case basis and considering the habitat’s size and habitat type of wildlife species present, it remains the developer’s responsibility to show adherence to applying BNG requirements in the right places, so it would be advisable to start thinking about the potential impact on biodiversity and wildlife habitats in the early design stage of development planning.

An Explanation of the Mitigation Hierarchy

As shown in the image above, the first step in the mitigation hierarchy with any identified potential damages to biodiversity is to minimise impact. If this isn’t possible, the second step would be to mitigate the impacts and prevent them from being as damaging. In circumstances where this also isn’t possible, the ecologist will suggest moves to entirely avoid impacts or step up habitat management to return the site to an earlier habitat state.

At this point, if it isn’t possible to minimise, mitigate or avoid the environmental impact of seeing BNG delivered via on-site gains, the ecologist will be left with no choice but to make off-site enhancements on suitable sites that are identified using the national register and separate from the current approach to development work – such as developing a plan for new habitat creation or enhancement away from the site – to meet the mandatory BNG criteria.

Delivering BNG Plans in Other Areas

Creating applicable local plans for the permitted plans for developing land or buildings involving the necessary level of ecological expertise may be subject to adverse impacts and vary depending on the nature of the site or key components of the habitat’s distinctiveness. For example, further strategic significance could apply if the site holds ecological importance locally or if the impacts on important habitats are drastic and the projected environmental benefits are limited.

Likewise, a development site with local importance such as a listed Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) or a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSI) may be treated differently. Other considerations that could make it harder to achieve BNG include the following factors, such as high numbers of irreplaceable habitats, crossover with another legal requirement, major applications for large projects involving multiple developments, and aims to leave the natural environment at the minimum BNG requirement as part of marine net gain in a marine development.

What if delivering biodiversity net gain makes the economics of my site unworkable?

Revert back to the example above: your site was assessed by an ecologist pre-development and they calculated biodiversity net gain on the site as being set at ten units, as determined by the relevant biodiversity metrics. The proposed scheme will therefore need to deliver a post-development score of 11 to reach a suitably better state of biodiversity value.

Perhaps you don’t have the gross development value (GDV) in your site to redesign the scheme or reduce the number of units to meet the net gain requirement using the most recently launched statutory biodiversity metric 4.0. So, now assume for the sake of example, that your final scheme can only accommodate just four units. Net four units off eleven and the metrics assign a deficit of seven.

What now? Well, you needn’t panic

Although technically a last resort – because the mitigation hierarchy argues for avoidance first, then mitigation, then on-site habitat enhancement such as the option to create wildlife habitats or demonstrate the prevention of further habitat degradation – you can buy biodiversity net gain credits off-site as a form of what’s known as offsite compensation.

What are BNG Off-Site Credits?

What typically happens is this: say a landowner wants to generate a new income stream on poorly performing land.

At the same time, a developer has been given planning permissions for a scheme that cannot deliver net gain at the mandatory 10% bracket within the local area of the subject site, and thus, requires land outside of the development proposal to enhance as a mechanism for off-site compensation and the inability for BNG to be achieved on-site within the red line boundary of the development site.

The overlap of interests produces great opportunities for both parties, benefitting UK biodiversity and satisfying the local plan policy, the local nature recovery strategies and national policy sets.

There are several steps in the process, so follow along closely and we’ll explain everything you need to know…

Developers: 6 Steps to Buying Off-Site Biodiversity Units

Step 1 – The Ecological Assessment

In the first instance, a landowner who wants to produce an alternative source of income needs to get their own land appraised by an ecologist using the DEFRA metric 4.0 to demonstrate what biodiversity units are presently extant.

Then, a net gain plan needs to be drawn up to, again, demonstrate how many units are available. The difference between the two is the limited number of units that are available to sell.

Step 2 – The Legal Agreement

Next, a mandatory nature conservation covenant of at least 30 years is written into a legal agreement that codifies the net gain plan via provisions in section 39 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. This agreement covenants the landowner and their successors in title to ensure the success of the creation of new units and contains a recovery provision if the biodiversity gain plan is not adhered to.

The ecological assessment and net gain management plan are usually appended to the agreement, with gov.uk now allowing local authorities, public bodies and other organisations become a responsible body and create a conservation covenant.

Step 3 – Regulation

At this stage, the landowner now has a plan and legal agreement to deliver biodiversity net gain. The next step for moving forward is to approach the regulator: the local planning authorities.

For example, in Warwickshire, Warwickshire County Council hold jurisdiction over decisions regarding a planning obligation.

If the local authority is satisfied that the net gain is achievable and appropriate, it will then recognise those biodiversity units officially (certification).

Step 4 – Credits

The words units and credits are essentially interchangeable at this stage. Once recognised by the land authority, the landowner can enter the open market to sell the newly created units (credits).

Ecologists – as well as land agents and specialist brokers – act as market makers for credits, connecting landowners and developers. The price for credits is determined by the open marketplace’s natural ebbs and flows that come with fluctuations in supply and demand.

As an alternative option at this stage, if it isn’t possible to reach a sufficiently positive impact on the site’s biodiversity but it also isn’t possible to refer to established third-party land, the developer can achieve off-site gains by purchasing the credits on a habitat bank somewhere else in the country.

Habitat banks are owned by land managers and facilitate an empty plot of land with a lack of habitats present for developers to meet the off-site BNG criteria.

Step 5 – Planning Consent

On designated sites that don’t qualify for an exemption, many developers may find attached to their planning approval are either conditions or a Section 106 agreement. The strategy is designed to commit the developer to making biodiversity net gain work, with the threat of enforcement or legal action for non-compliance with the planning obligations of the planning decisions of the local authority.

By buying statutory credits that are certified by the planning authority from landowners, the developer is immediately released from the Section 106 agreement or conditions of planning applications.

Step 6 – Post-Credit Purchase Obligations

After the transaction – as well as the payment of corresponding legal costs (normally paid by the landowner) – the developer has no further obligations to mandatory BNG. The landowner must, however, ensure that the net gain plan is followed exactly as covenanted, using the income from the credit sale.

As the legal agreement contains recovery provisions, if the biodiversity net gain is not at least 10% at the expiration of the long-term covenant and maintained for at least 30 years, the landowner can reasonably expect the local planning authority to take action.

Speak to Biodiversity Net Gain Experts

Following extensive experience and a vastly knowledgeable background in providing detailed new guidance and expert advice to achieve biodiversity net gain, encourage developers in the planning process and eliminate negative impacts, our team of specialist ecologists are correctly suited to meet the required increase and appease the biodiversity gain requirement on development sites, legally secured for at least 30 years.

Whether you suspect likely biodiversity losses of the irreplaceable habitat of a protected species feature on your site, or you simply want an expert to implement a BNG plan at the report stage to enhance biodiversity, satisfy the relevant local planning authority and achieve a planning condition as you look to complete a project to develop land or existing buildings, we are here to help.

Reach out to our team by visiting our contact page or calling us using the number at the top of this page, and our friendly team will be on hand to support you in your mandatory biodiversity net gain needs and reach the enforced planning policies of the corresponding local planning authorities.

From the first glance of your project at the quote stage to developing a full picture during the specific duty of attending your site for an assessment, we will hold the same good practice guidelines and provide feedback that prevents habitat loss, both for private householder applications on small sites and commercial applications on large sites.

Further Biodiversity Net Gain Guidance

Additionally, for more detail on the Environment Act, the prior Environment Bill, government policy, protections, legal implications and existing legislation and relevant secondary legislation, ongoing Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS), the Nature Recovery Network (NRN) and the Natural Capital Committee (NCC), and the involvement of key stakeholders, local decision-makers, local authorities, the general public, land owners and bodies such as the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and Natural England / Natural Resources Wales, we answer more questions on implementing BNG on our biodiversity net gain Q&A page.

Here, you will also find new BNG guidance and further detail on biodiversity net gain assessments, calculating biodiversity net gain, delivering net gain, conservation covenants, and the current biodiversity metric.